Press Release

This is a highly unusual approach. Wang Jianwei’s solo exhibition “Cambrian” was split into two, and presented at the West Coast Art & Design Fair on November 7th and ART021 on November 8th. Moreover, Lu Jie, the founder of Long March Space, insisted that this is not a solo exhibition of the artist displayed in the booth of the art fair, but a solo exhibition of the artist originally located in the gallery, split into two, like a serialized drama, and put into two successive openings of the art fair. In this exhibition named “Cambrian”, all the works are dyadic, coincidentally constituting an even number of pieces, so that the two art fairs’ Long March Space exhibition halls are like mirror images, equally divided in the way of “half an exhibition”, each half.——LiuXujun

In its slumber, geological time may hold knowledge that we even now may be unable to get to the bottom of.

This is not only because of how we hold in awe the unimaginable span of geological time, but also because we fear the inexplicable shortness of human life and time. Geological time completely transcends how “we” usually measure the world, going past how human eyes can hope to perceive everything on the earth.

A brownish chunk of ore, a drop of shale gas, a handful of rare earth: these become the turbines of airplane engines, the tracks for high speed trains, the transmission towers that carry electricity for thousands of kilometers. These materials not only possess the authenticity of metal and energy, but also, in terms of how they are distributed across the earth, have a geographical integrity, concurrently occupying the reality of different time periods and producing different energies. These energies leave us at a loss of what to do.

Geological time is not simply part of geological science, it is about the residual knowledge held in the tension between vertical and horizontal orientations. Because we have not fully grasped the connection between the “long term” within these layers and levels and how we use their resources in the present, we are already aware that our identity today is as “users”, and mediating between our physical bodies and this role of the “user” there is a hidden undercover agent from the “long term”— sediment from 100 million years ago that has become embedded between us and the world. Compressed, it serves as part of the humble microchip that has become the master of this new world. This chip has given us an enhanced version of reality and super speed connections, but at the same time thrown us into an abyss that is beyond our comprehension.

This makes our imagination and the grand narratives we rely on look pale and weak. We can only cling to the comparatively legible metaphor of “the cloud” to console ourselves for our inability to grasp these unfathomable algorithms, yet at the same time we are grateful that technology has granted us a new “individuality”. The vertical orientation of the “stack” directly meets the new technics (algorithms), redefining individuality and its form, automatically creating a new body shaped by chance.

This is a new composite body, as the user serves the vertical system through an interface, and the system is only completed by the presence of the user. A new way of doing things is born through its usage. It can be understood as the method of the user, a highly effective method, which cannot be passed off to a representative. It is a game between vertical and horizontal, blocking the usual flow of things and forming a sort of obstacle. This hindrance is caused by the fact that we cannot open up each layer vertically, cutting through into the boundaries of our cognition. Minerals and their physical sources can no longer be defined merely by the geological level they exist within. Eventually this presents a paradoxical present and future.

A concrete thing itself already presents the richness of material, and not just as a projection of the outside world. A painting is a device and a world unto itself, containing all the things that appear on this planet; just like the world we face in this present moment, thick with meaning and growing all the time. Any specific event arises from uncertainty, and any discernible scene is usually divided into different fields of knowledge. We often say that A and B are related and discuss why they are connected; but this logic underpinning our values of what constitutes a rich and fertile earth may be only be a guess, just because the two variables happen to exist in the same “framed” image, with no reason to bear responsibility for a shared subject. Perhaps it is just chance that they occur at the same time, at the same place. Traces accumulate in their own way, leaving behind incomplete evidence, while elsewhere these traces find another way to relate to each other. This is like when we cross the road: we are in the same “frame” as the other passers-by rushing around us, but we do not assume an aesthetic responsibility for the scene. The gathering is purely coincidental. Perhaps this is like the work of painting today, determined by the fortuitous meeting of time and form.

This is like how we are willing to discuss “society”: every person exists in a different channel of society, and it is filled with differences and inequalities. We cannot say it is simply an “individual” unified thing, as experience of society depends on how you encounter it. So we cannot reach a consensus on society (this attitude itself is full of differences, and it is precisely these differences that bring society closer to reality). Similarly, when you face specific things (such as paintings and installations), there is actually no shared understanding, only a shared time.

Literally speaking, it is hard for us to face and understand a world where everything is unrelated. It seems that all wealth, complexity, and possibility is built on relationships between different factors. But in fact the world is not as prosperous as we imagine — or perhaps the connections between things are richer than we imagine, only they are linked by different means than we expect. So we often fall into dilemmas that we have no way to describe. We cannot use our pre-existing knowledge to grasp these situations. More and more relationships revolve around this object-time nexus, yet the things themselves have already vanished from the scene. The causes and consequences of the life of things from beginning to end can never be mutually criticized (except under false testimony). Should an art object, or to be more precise, a technological thing that grows in time, go farther than our prior suppositions, or rather beyond our knowledge?

The boundaries between “foreground” and “background” are already blurred. Maybe if we go into the surroundings behind clearly defined things, we may discover that the “background” itself has its own relationships, and not those we choose for it, no matter which theory or meticulously outlined practice we place over reality (searching to find what we have already planned to see, like the intellectual equivalent of destination tourism). We cannot grasp all the connections underpinning things in one swoop: they are omnipresent, and cannot be placed ahead of time or summarized afterwards. The branches and needles of a pine tree, a mass of earth and the man-made dam it supports, the natural phenomenon of the exploding cloud and its endless continuity, or a machine in operation and its mottled paint… these things are part of the object itself, escaping from the entanglement of surface meaning (a human endowment), and becoming the main body of the object.

These new actors and technology conspire together to reorganize “nature”: algorithms determine the clarity of mountains, and filters add a “natural” reality. A mountain, a river, a cloud — they all come from the hands of a microchip, and the particles of this chip come from blades of grass or the shell of an invertebrate creature that suddenly disappeared in the Cambrian Period. The distant past determines our now, and what is underground controls the sky. Because of their presence we must not become too confident.

Wang Jianwei

September 24 2018

Artworks

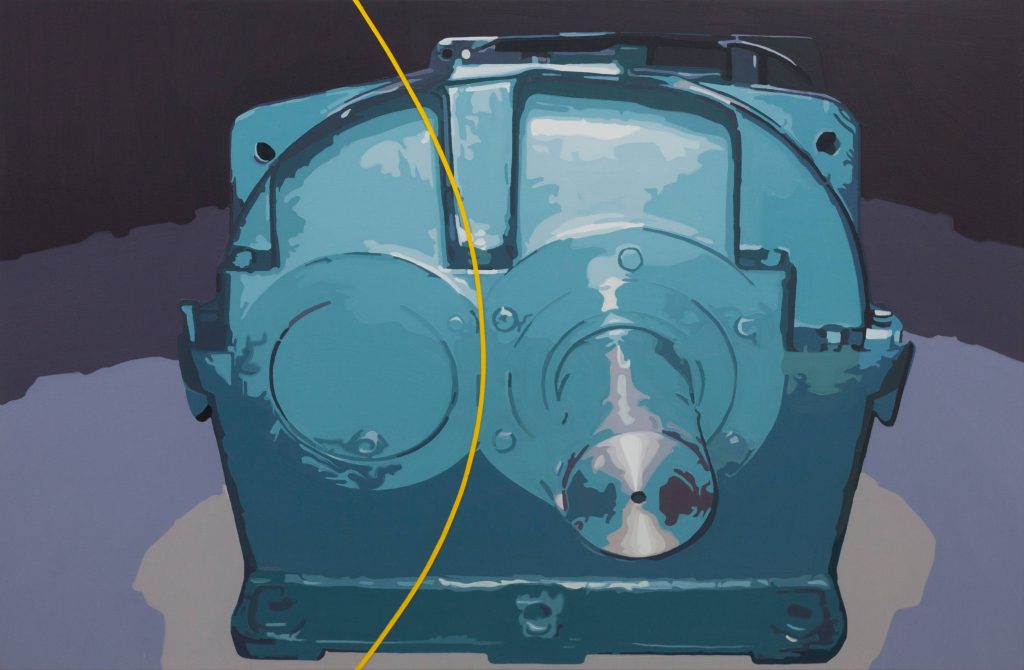

Cambrian

Acrylic and oil on canvas

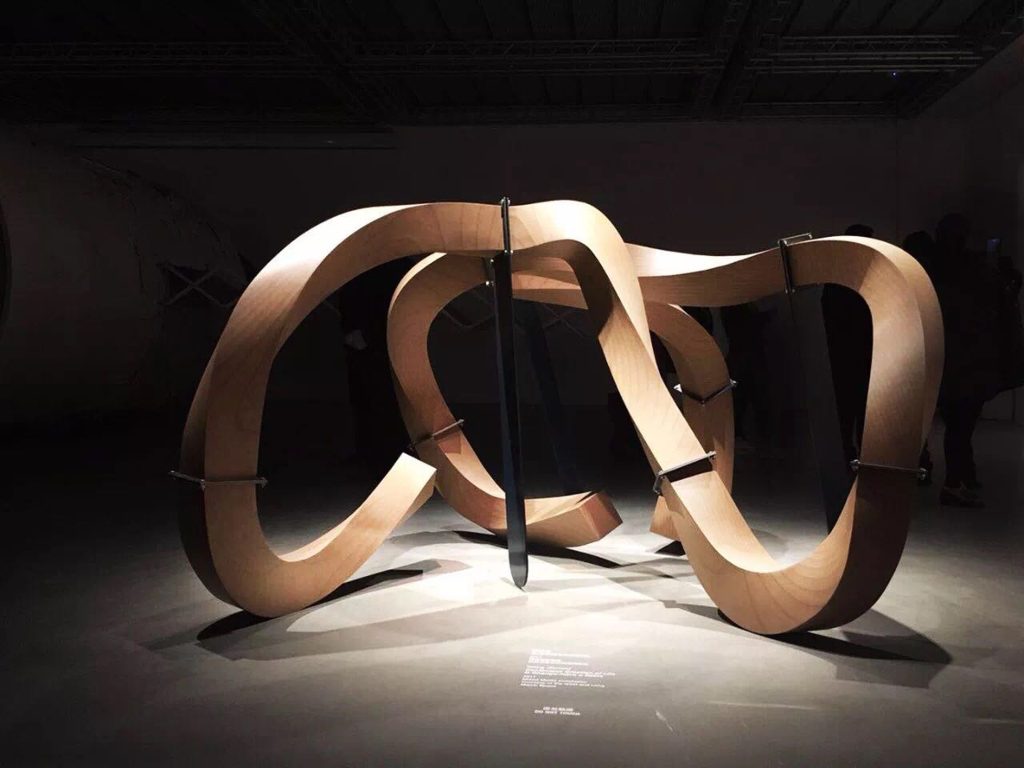

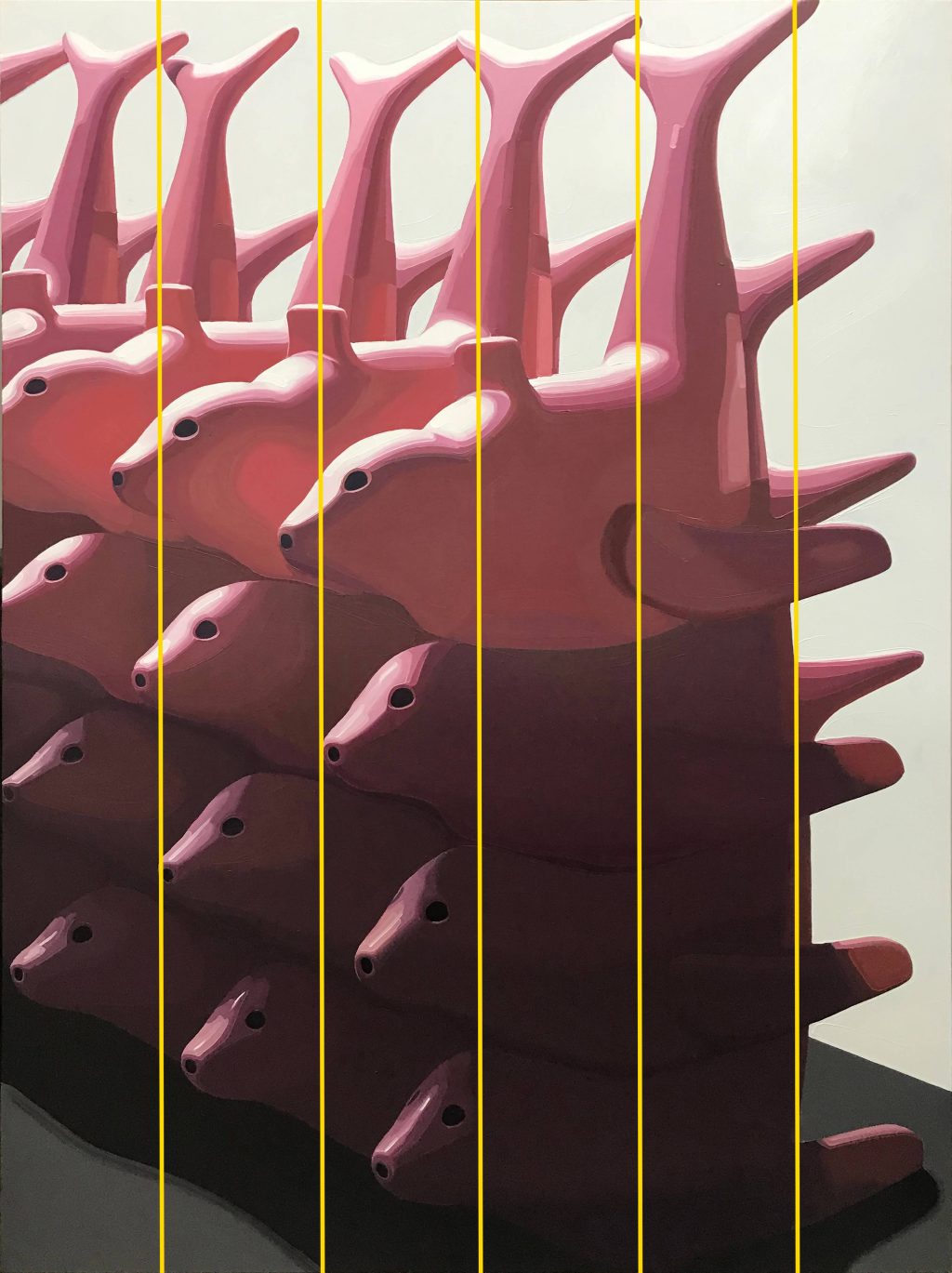

Continuous creation of life is change- Have a spine

Wood, metal, spray paint

114 1/2 x 102 3/4 x 56 1/4 in. (291 x 261 x 143 cm)

Cambrian No.4

Wood, spray paint, stainless steel

95 1/4 x 70 3/4 x 28 1/4 in. (242 x 180 x 72 cm)

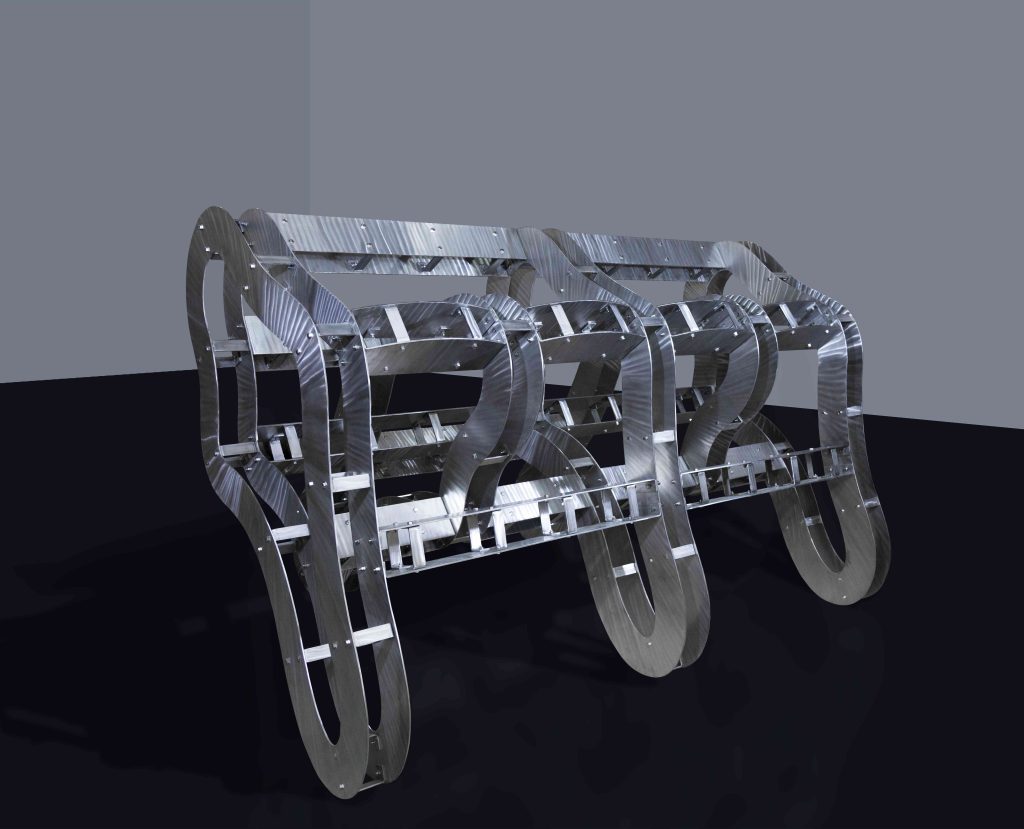

Cambrian No.6

Stainless steel

61 x 94 7/8 x 56 5/8 in. (155 x 241 x 144 cm)

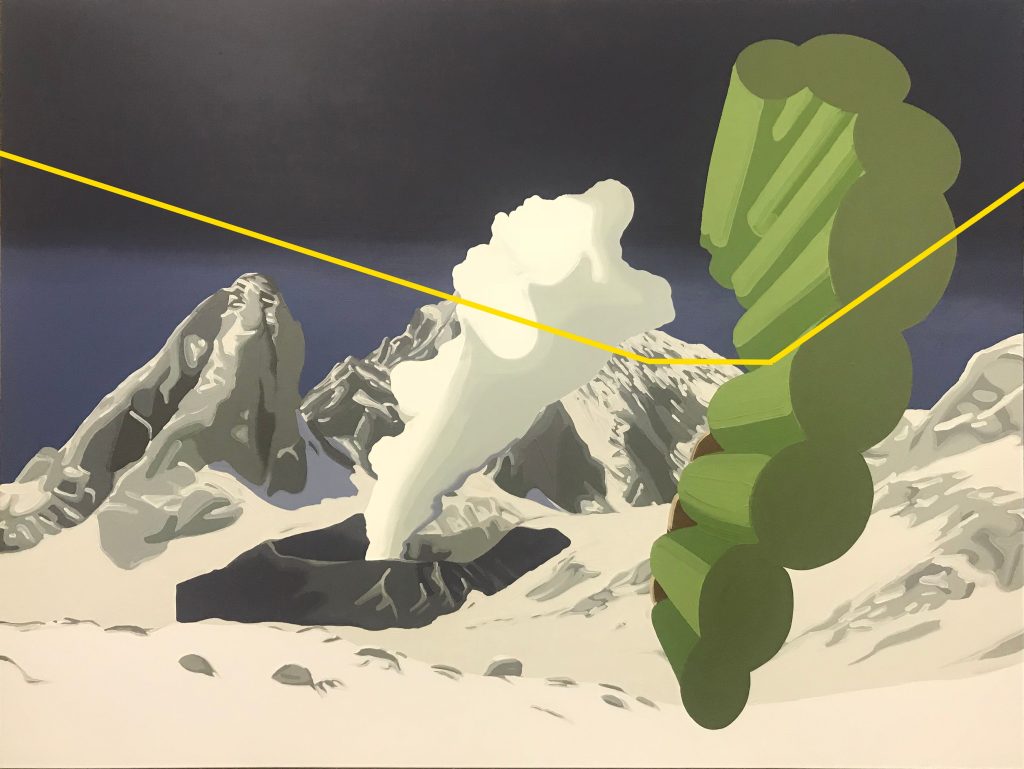

Cambrian

布面丙烯、油画

Cambrian

250 x 187 cm

Oil on canvas

Related

Group Exhibition

Chengdu-Pompidou: International Art Biennale of the Global City

Sichuan Province, China