- -+

Eliminate prejudice : Wang Jianwei’s Historical and Political Narrative

Huang Zhuan

Monk Zhao’s “Discourse on Non-Vacuum” uses the Middle Way to solve the problem of existence and non-existence, the Lord does not cling to existence or non-existence, non-existence and non-existence, if and when, aiming to lift the obstacles to all knowledge of certainty, and observing the world and life in such a way and with such an eye is called breaking the clinging.

Wang Jianwei has never used this term, but his art philosophy has never lacked similar dialectical wisdom:

If there is some kind of tendency in my works, I will be very wary. I’m interested in ambiguity and uncertainty. …… Uncertainty itself is control, it limits your work from showing some kind of strong tendency, (prompting you) to abandon the narcissistic, chest-thumping, confident, accurate way of thinking, and to make questioning the starting point of your work.

Skepticism may be the nature of contemporary art, but Wang Jianwei often reminds himself not to turn this nature into an abusive moral impulse, preferring to keep this skepticism in a somewhat neutral state, so as to keep enough gray area between observation and object – his favorite word – so that skepticism becomes a kind of exploratory wisdom. -thus making doubt a cognitive process of intellectual inquiry rather than an expression of thought or a statement of political position, as Susan Sontag wittily put it when talking about contemporary art and thought as a new form of mythology:

Art is not an idea in itself, but an antidote that develops from within the idea.

1 History and Politics

In Wang Jianwei’s works, history and politics are two themes that are either juxtaposed or intersected, but rather than examining the authenticity of these two themes, they are more like two “discourses” or “cases” of Zen enlightenment, which hope to lead us into the trap of questions rather than the end of facts or truths. It hopes to lead us into the trap of questions rather than the end of facts or truths.

2 Screen

Composed: 2000

Premiere: 2000

Premiere Venue: Beijing Seven Colors Children’s Theatre

Created in 2000, The Screen is Wang Jianwei’s first real – in terms of its having actually been performed – theater work, and its plot lines and narrative structure are somewhat similar to those of Kafka’s The Trial, although its obscurity and humor are not Kierkegaardian but Wittgensteinian. It is a bit like Kafka’s The Trial, although its obscurity and humor are not Kierkegaardian but Wittgensteinian.

The story stems from the author’s reading of a “loophole” in the history of Chinese art, where the dual role of Gu Ma-zhong, author of the famous painting of the Fifth Dynasty, “The Night Banquet of Han Xizai”, as a painter and as a spy, provides a great historical imagery and the conditions for re-reading:

The process of the “screen” is both an “archaeology” of history and tradition, and an “archaeology” of our own methods of “reading” history. “As Wittgenstein said, “The most important aspects of things for us are hidden by their simplicity and familiarity”, and there is nothing more familiar to us than art, which has been “read” for almost a thousand years. What has been hidden?

The fictionalized plot around this hypothetical question is like a jumble, and the “case” begins with a group of Southern Tang painters talking about an interrogation “in waiting,” and it is extremely unclear who is being interrogated, who is being interrogated, and what is being interrogated, even if it is not clear:

We can’t prove whether we are waiting to be interrogated or to be questioned.

In the second act, the relationships between the characters seem to be clear, and the interrogator’s body check of the interrogated Gu is highly empirical (28 physical signs): from height to eyesight, from scars to skin type, from deformities to body odor, but what follows makes the “reading of history” ambiguous:

GU: If, as you say, I was arrested by you, why wasn’t I tied up by you, and how can I prove that I was arrested when I wasn’t handcuffed?

Diff: We never use those.

GU: Then I can’t prove that I was arrested.

Diff: I’m only responsible for making the arrest, not for proving you’re under arrest, that’s the next procedure.

GU: But I can still go in and out of my room, watch TV, make phone calls, I have a key, I can go to work? You’re like a machine.

DIFFERENTIAL: I’m also not responsible for hearing your personal thoughts. Also. If you insist that you’re not Koo, you’re not under arrest, we’re arresting Koo. (errand boy steps down behind screen, gu transmogrifies as John Doe) (lights darken scene)

In this way, a trial with a clear legal relationship is turned into a comical sophistry, and the defendant’s “spin” makes the next scene even more bizarre, turning the trial into a “description”, “reminiscence”, “defense” and “mutual proof” of all the characters, and the chaotic mix of ethics, art, justice, and personality issues makes the reading and examination of “history” hopeless. The interrogation becomes a “description”, a “recollection”, a “defense” and a “testimony” of all the characters, and the chaotic stirring of ethical, artistic, justice, and personalities issues turns the reading and examination of “history” hopelessly into a language game. The reading and examination of “history” has been hopelessly transformed into a language game that follows not the logic of history but the paradox of “rule-following” revealed by Wittgenstein: if any course of action can be interpreted by itself as conforming to a rule, then the rule cannot be – in the practical sense – a rule, but a rule that is not a rule. In the practical sense, rules cannot be rules, and in order to maintain them we may have to revert from the logic of language back to history.

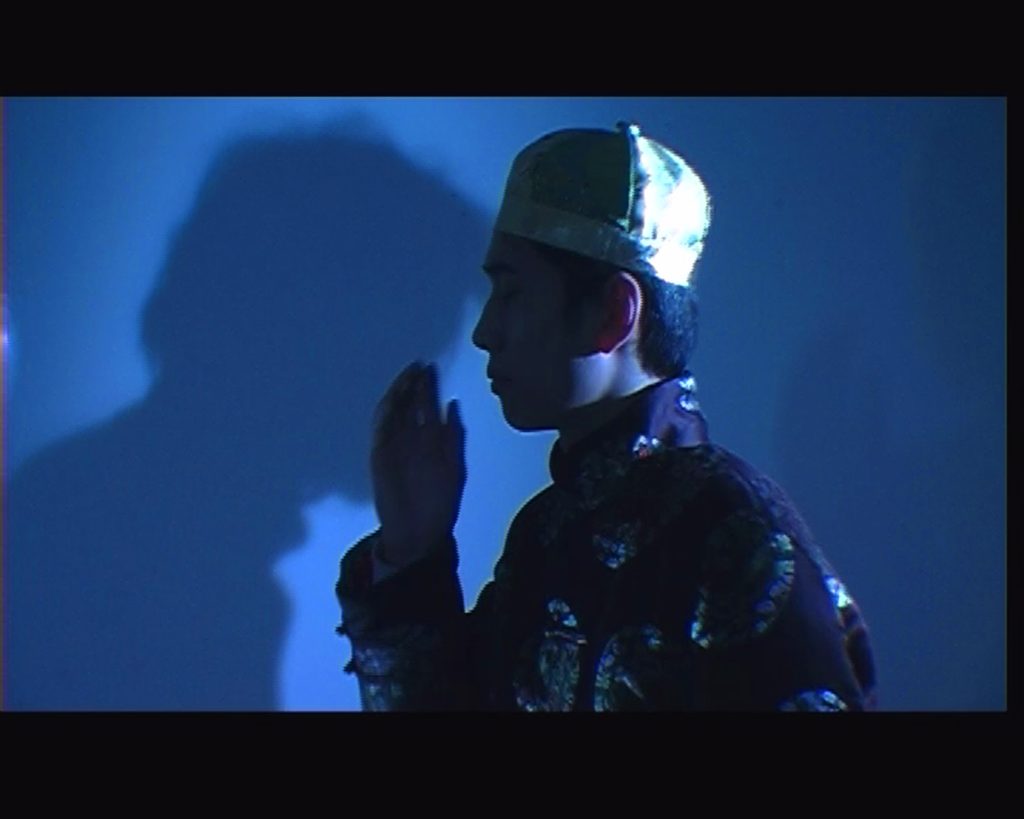

3. Ritual

Composed: 2003

Performed: 2003

Premiere Venue: ICA, London, UK

In 1923, Gu Jiegang became famous in the historiography world with his “theory of ancient history in layers”. Unlike the ancient scholars of the Qing Dynasty, who were famous for their skepticism of ancient history, this theory no longer aims at examining a certain ancient history, or even identifying the authenticity of history, but argues for the overall history of the ancient world, that is to say, how the story of “since Pangu started the world, the three kings and five emperors have come to the present day” has been fabricated by the Han Confucianists, which is the scandal of the history of history. Fusnian has made this historiographical scandal a reality. Fusnian compared the value of this historiographical speculation to the contributions of Newton to mechanics and Darwin to biology.

Ceremony is another of Wang’s major historical narratives, and here the “test history” uses a method similar to the “layered theory,” a methodological experiment with historical texts that still examines the possibility of open-ended readings of historical texts.

Cao Cao and You Heng are a pair of asymmetrical characters, linked by the ethical story of “beating the drums to scold Cao”, which is a latent historical story of the Han-Wei orthodoxy dispute, and the character of You Heng becomes more and more “real” through the three historical texts that are separated by thousands of years (The Book of the Later Han Dynasty (Hou Han Shu), which is the official history; Romance of the Three Kingdoms (San Guo Yan Yi), which is a folkloric novel and drama; and The History of the Wild Drums of Fisherman and Yang (Yu Yang San Lang), which is a folkloric drama). The process by which this character becomes more and more “real”, enriched and ordered through the three historical texts (the “Romance of the Three Kingdoms” as the official history, the “Folk Novel and Drama”, and the “History of the Wild Drums and the Three Rhymes of Fishing and Yang”) thousands of years apart, hints at the non-linear nature of history.

The “ritual” is an open-ended historical reading, which Wang says has two meanings: the textual meaning of the story of “beating the drum” as a ritual, and the methodological meaning of the ritual as a form of historical narrative, which aims to examine the “drumming and scolding Cao” as a form of historical narrative. It aims to examine how such a historical “event” as “beating the drum to scold Cao” and such a symbolic image as “You Heng” were fixed through the accumulation of writing practices. In my opinion, it should also have a third meaning, which is how the ritual itself is endowed with a transhistorical power through self-evident ethics and power, as in the case of the Zhou ritual in ancient China.

The identities of the characters in Rituals are even more ambiguous and vague than those in Screens, referred to only by A, B, C, D. The masks exacerbate the uncertainty of the identities, as they are at times the masters of the historical stories (e.g., You Heng) and at times the peepers into the mysteries of the histories; at times they are the tellers of the historical stories and at times they are the listeners of the historical stories. All the discussions have only one theme: how individual people are remembered by history, and while the discussion is destined to end fruitlessly, it demonstrates an intellectual method of breaking the spell of history.

4 Birds of Prey Don’t Move

Created: 2005

Performed: 2005

Premiere Venue: Arario, Beijing

Birds of a Feather deals with an “abstract” philosophical theme, exploring what Bergson called the primary problem of metaphysics: time. The work uses the famously sophomoric proposition of the ancient Greek philosopher Zeno, but gives it a new historical metaphor.

Unlike Screen and Ceremony, Birds Without Moving takes the form of an abstract historical narrative. In this work, the comic book version of the Yang family’s story, “The Double Dragon Society”, is deliberately “fragmented” and “framed” as a reading experience by the author, which wants to illustrate that the “moment” is also an effective way of reading history: the “moment” is also an effective way of reading history: the “moment” is the “moment” in which history is read. is also an effective way of reading history:

The whole project of Birds of Prey was created in a completely closed space, in an “isolated” atmosphere, with no specific time, but with a clear space, no specific purpose, but with a specific object. The whole event takes place and develops according to a classic Chinese martial arts pattern, mixed with each “actor’s” understanding of the “role”, …… In this specific space, the original complex historical relations are reduced to a continuum. In this particular space, the original complex historical relationship is reduced to a continuous action. ……The moment provided by the space is a “temporary” history without depth. ……The openness of the space makes the meaning of the space uncertain. The openness of …… space makes the meaning of the space uncertain. …… This comprehensive and non-linear narrative provides new possibilities for the image.

History is abstracted, and this abstracted history becomes a medium for us to understand history.

5 Theater

Theater is the key word that explains Wang Jianwei’s aesthetics. For Wang, the choice of theater as a narrative medium is almost as much a methodological necessity as the choice of images (film, video, television). Wang once defined a contemporary form such as “multimedia” as three related aspects: overlapping spaces, technologies and tools, and, most importantly, integrated knowledge systems and non-linear narratives, with the theater as the “site” that carries these concepts I think the real significance of ‘theater’ lies in the fact that it is a site of transformation and meaning-making.

It is through the “theater” that Wang Jianwei establishes an anti-dramatic mode of dramatization, in which the author does not need to set a meaning for the work, nor does he need to reserve any extra meaning, as if the structure itself has the energy to constantly change or create “meaning”, and the text has the energy to change or create “meaning”, while the text has the energy to change or create “meaning”. It is as if the structure itself has the energy to constantly change or create “meaning”, and texts, plays, films, installations, performances, as well as any props, performers, participants, and viewers can all act as the makers of such open meanings without exception. The “voyeurs” who are witnesses to the events in Screen (they are invisible and ever-present), the Chinese characters that are constantly scattered in the background video of Ritual, and the audience who are performers in Hidden Walls are constantly harassing, disrupting, and even aborting attempts at any definitive reading of the work, providing the kind of indeterminate reading that the author hopes provide the kind of indeterminate reading pleasure that the author wants us to obtain.

6 The Hidden Wall

Composed: 2000

Premiere: 2001

Premiere: Weltkunsthalle, Berlin, Germany

Politics is usually a discussion about truth and justice, but in the open narrative structure of “theater”, the political stories told by Wang Jianwei usually deviate from this theme and become some kind of intellectual game. Hidden Walls is one such game.

The opening ceremony of the official Contemporary Art Fair in Berlin, a scene with a strong political odor, constitutes the organic context of Hidden Walls, and Wang Jianwei decided to add another opening to it: a more politicized one. The result: the two openings with the same program end up as a double metaphor whose meaning cannot be determined and controlled.

7 Signs

Year of creation: 2008

Premiere: 2008

Venue: OCT Contemporary Art Center, Shenzhen, China

The theme of Signs is about the production mechanism and process of how the “body” evolves into the “individual”, which consists of a group of video and photo works and a large sculpture in the form of a recumbent mushroom cloud of a nuclear explosion in China in 1962, the source of which is the author’s fragmentary historical memory. The sculpture is the lying form of the mushroom cloud of the 1962 nuclear explosion in China, which comes from the author’s fragmented historical memory, while the video part of the work creates a simulated “archaeological” site, the illogical jumble of history and reality, according to the author’s statement, is intended to provide art with a method similar to the anthropological method of “offsite investigation” and to form a way of thinking that interrogates each other. According to the author, he hopes to provide art with a method similar to anthropological “ex situ investigation” and form a way of thinking that interrogates each other.

The time structure of this work is linear: from ancient China to modern China, but it disrupts the possibility of linear interpretation of this time structure by setting up several sets of contradictory relationships, in which the biological body and the social body, the class crowd and the economic crowd, and the fictional reality and the real history are all united in an interdependent and mutually controlling network of relationships.

“Signs” is a medical term that Althusser borrows to illustrate the theoretical way of examining ideology. In his view, in the pluralistic relationship between art, ideology, and science, art cannot provide precise knowledge about ideology as science does, but can only provide symptomatic observation and life experience, and the critic’s interpretation of artwork can only be a symptomatic observation and life experience. It can only provide a symptomatic observation and life experience, and the critic’s interpretation of the artwork can only be through “symptomatic reading”, examining the ideology in the “silences”, “gaps” and “omissions” of the art text. The critic can only examine the controlling instincts of ideology through “symptomatic reading” in the “silence,” “gaps,” and “omissions” of the art text.

Critics read ideology through art, while Wang Jianwei hopes to read history and politics under ideological control through his art.

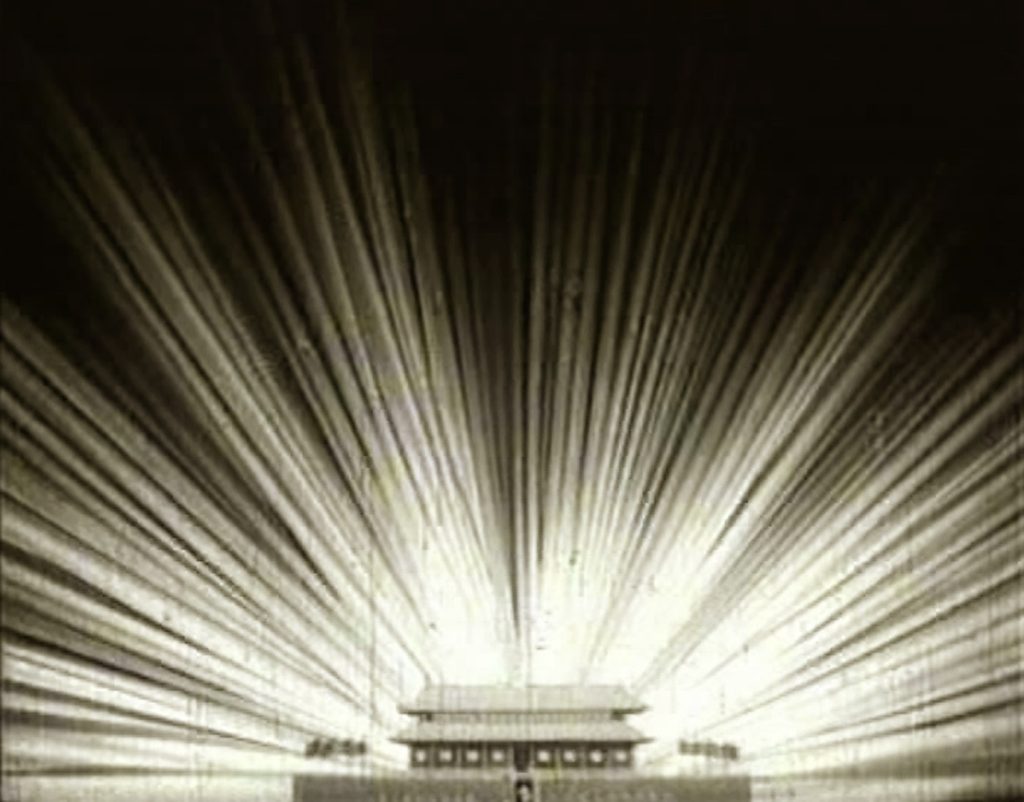

8 The Observatory

Created: 2009

Premiere: 2009

Venue: Manchester Metropolitan University, UK

Unlike his previous works, Wang prefers to refer to this work as a “study,” and in fact, although this study, which began in 1997, has been shown in two different forms in the United Kingdom and Shenzhen, he still considers it to be an unfinished work.

Tiananmen Square is the largest and most important political space in China, and as the “heart” of the republic, almost all of its functions are symbolic and ceremonial, while its connection to the ancient Chinese empire extends the historical dimension of this symbolic space, all of which cannot fail to touch Wang Jianwei’s sensitive nerves:

…… One of the most important aspects of architecture is the “relationship”, and (this) relationship sometimes leads to a large extent to the stylistic and other aspects of the building, which is not a problem to be solved within the history of architecture and art, but it is a problem that I am interested in and that is the reason for this work. This is not a question to be addressed within the history of architecture and art history, but it is a question that interests me, and it is the cause of this work.

The focus on the Observatory began in 1997 with the project Architecture of Everyday Life, which was part of Wang Jianwei’s research on “spatial history,” which, like his other projects, stemmed from his interest in the conditions of knowledge and power in the production of visual space. His observations on the Observatory are almost archaeological in nature: its own history as a building (its designers and design history, its proportionality to the other buildings in the square, its history of use), the relationship between its architectural, visual, and symbolic functions, and even its “body-political” attributes (who is allowed to be on the Observatory, who they represent or symbolize, and what they do through the Observatory). who can go up to the Observatory, who they represent or symbolize, and the process by which they become such symbols).

In his original proposal for The Observatory, Wang’s methodology was analytical: an anatomical transplantation of the original Great Observatory cut up into similar political or religious squares around the world, perhaps with the idea that such a reproduction might lead to an accretion of meaning:

I am particularly interested in taking every part of the text formation process and reproducing it, …… so that in that way there can be a sense on the spot of some kind of relationship between real knowledge and visual culture. …… What I am interested in right now is the history of the text and the history of the text these I am now interested in the text of history and the history of the text.

This project was realized in a slightly different way at the National Heritage exhibition at Manchester Metropolitan University in 2009, where the Observatory, as a kind of “ideological heritage”, was transplanted as a computerized 3D interactive simulation image in collaboration with Norman Foster UK. In collaboration with Norman Foster, the Observatory as an “ideological legacy” was transplanted to Manchester as a computerized 3D interactive simulation image, and in the following exhibition of the same name in Shenzhen, the Observatory was enlarged to the scale of the 3D modeling of Manchester to become a solid architectural skeleton. This history is more like a re-opened and multi-readable book, which is perhaps the intellectual significance of contemporary art that has always been neglected by us.

2009-11-5

Related Artworks

Related

Solo Exhibition

Symptom: A Large Scale Theater Work by Wang Jianwei

OCT Contemporary Art Terminal of He Xiangning Art

-1-1024x683.jpg)